Jesse Singal strikes again. In his most recent article, he reports that the “growth mindset” theory (and raging fad) has “staggeringly little evidence” to support it. The actual research underlying it appears incomplete and flawed. (Note: Singal later corrected his assertions.)

Jesse Singal strikes again. In his most recent article, he reports that the “growth mindset” theory (and raging fad) has “staggeringly little evidence” to support it. The actual research underlying it appears incomplete and flawed. (Note: Singal later corrected his assertions.)

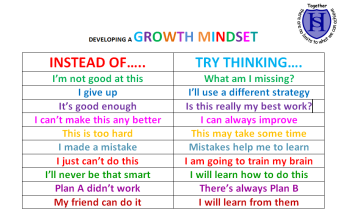

Carol Dweck coined, investigated, and popularized the theory of “growth mindset”: namely, that those who value improvement and persistence tend to be the ones who ultimately excel, while those with “fixed mindset,” who expect themselves to succeed right away, tend to quit at the first sign of failure. Schools have seized on this, telling teachers not to praise students for their talent or even their accomplishments, but rather for their growth. Supposedly, if students start thinking in terms of growth, they will set themselves on a path of continued improvement.

There is some truth to this. You don’t do a student (or anyone) a favor by continually saying “you’re so smart” or “you play beautifully.” On the other hand, if you force yourself into growth-mindset lingo (“You’ve grown so much since your last recital; your staccato is much more precise than before”), you don’t help anyone either. This kind of dogmatism becomes a fixed mindset of its own.

In addition, if you devote school resources to the cultivation of “growth mindset,” you may take away from other things, such as literature, mathematics, music, and so on. Moreover, attempts to incorporate “growth mindset” in the curriculum can lead to rigid and limited interpretations of the subject at hand.

For example, the 2016 study “Even Einstein Struggled” (conducted by researchers at Teachers College and the University of Washington) compared ninth- and tenth-grade students who read “struggle stories” of scientists with students who read “achievement stories.” It found that those who read struggle stories, especially low-performing students, saw a greater increase in their grades (which were based on “classwork, homework, quizzes, projects, and tests”) than those who read achievement stories. In addition, it found that students who read the struggle stories felt more connected to the scientists than students who read the achievement stories.

But the researchers do not consider the possibility that a “struggle story” may be intellectually interesting as well as emotionally satisfying. Students may connect with it not just because they can “relate” to struggle, but because they want to see how a scientist solved a problem.

After all, that is what scientists themselves think about, a good deal of the time. In his illuminating (and wonderfully unfaddish) book How We Reason, Philip Johnson-Laird argues that it was not simply persistence that eventually brought the Wright brothers to success, but their particular way of reasoning through errors. It is not accurate to say that they succeeded because they “never gave up” or (in growth mindset parlance) believed they could “get smarter.” I doubt they were thinking about their brains.

Another pitfall of the “growth mindset” is that it gets awfully silly awfully fast. You start seeing posters with “growth mindset praises.” You are told never to call a person smart. NYC Educator comments on such dogma:

I don’t freely call people smart. I really say that to very few kids. But if I say it, it means I’ve noticed something very special in them. Kids who think fast, who come back immediately, who aren’t afraid to say directly what’s on their mind, and who have clever, creative or impressive things on said minds really impress me. I have to tell them how smart they are. I never know whether or not anyone else has told them, whether anyone else has even noticed, and I think they need to know.

I don’t tell students they are smart, but I have told them when I thought they did something especially well (another “growth mindset” no-no, according to some). I wouldn’t do that all the time; that would give my praise too much weight. But I wouldn’t abandon it either.

I think of the times when someone has recognized my work–for its quality, not its growth. Some of these praises were pivotal in my life; they helped me see that my work could affect people. I didn’t stop working because of that. Yet I also needed people who could point out flaws. Over time, I became able to do much of this for myself–recognize when I was (or wasn’t) doing something well, and identify what I could do better.

Also, there are things I simply am not good at (like improv comedy). Sure, I can “grow” in them, but is the slow crawl toward mediocrity worth my while? It may actually help me, in some circumstances, to utter the forbidden phrase “I’m just not good at this.”

Like many ideas in education, growth mindset theory expresses a partial truth. It is neither revolution nor royalty; it deserves neither chants nor a crown. On the other hand, the “takeaway” is not that we should get rid of all vestiges of growth mindset. Take away its dogma and buzzwords, but give it a modest place among other principles.

Image credit: HR Zone.

Note: This was a preliminary piece on the topic; I edited it several times after posting it but left it mostly intact. See my later pieces “Are Mindsets Really Packageable?” and “The Benefits of Complex Mindsets,” as well as a chapter in my book Mind over Memes: Passive Listening, Toxic Talk, and Other Modern Language Follies.

5 Comments