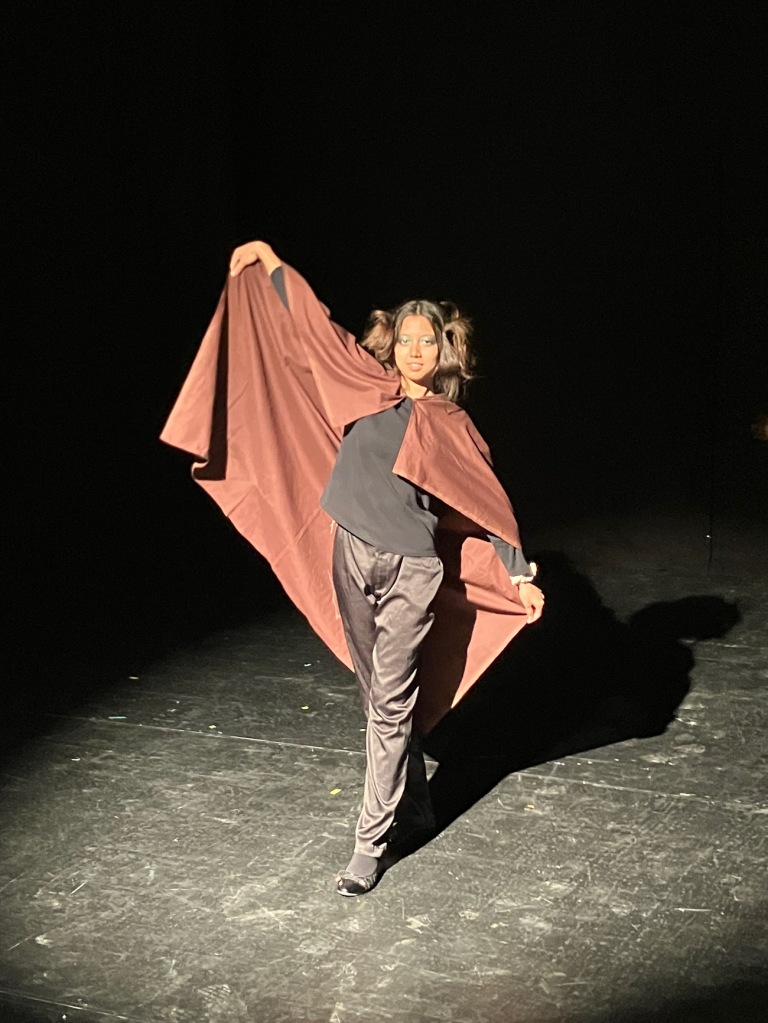

I’ve taken a picture like this one before, but this one, from yesterday’s event featuring special guest János Másik at the Cseh Tamás Exhibition at the Petőfi Literary Museum, came out even better. Here the character Vizi (from the Frontátvonulás performance and album) holds up a glass, which he will then release. (His figure is a shadow here.) In the story, the glass stays in the air. When Cseh performed this, he would release an actual glas glass. Even though it fell to the ground and shattered (it had been prepared to do just that), through the power of suggestion it seemed to float in the air, according to accounts.

It feels strange that yesterday was my sixtieth birthday; it’s a little like holding up a glass, releasing it, and seeing it float in the air. The implausible seems to be happening at any given moment. Things are clapping together like thunder. Projects, friendships, teaching, everyday life. Even eight years ago I had no idea that any of this was to occur, and the surprises keep coming. But I am also aware of not being thirty, forty, or even fifty any longer. Behind the floating glass, there’s also a glass that crashes, if only because I get tired more easily and more obviously.

I have been thinking back on these six and a half years in Hungary. There have been occasional twists and bumps, but they all led in the end to something better. Who would have known that I would end up at a school with two colleagues whose work I would end up translating? Or that my translations of a young Hungarian poet would end up published by five different literary journals? Or that through my forays into music, I would end up collaborating with two songwriters and a poet on an online Pilinszky event, and then invite them and others to take part in a seminar on “Setting Poetry to Music” at the 2022 ALSCW Conference at Yale, a dream that came about?* Or that, through taking interest in (falling in love with) the songs of Tamás Cseh and Géza Bereményi, I would start writing essays about them, two of which have now been published (and the third accepted for publication in July, and the fourth in progress)? Or that a Shakespeare festival would come about, through my collaboration with colleagues at Varga, the public library, and (this year) the local theatre, and that it would continue beyond three years? (Next year’s is looking to be majestic.) Or that I would reach a point where I could attend literary events and follow the entire discussion in Hungarian, not just bits and pieces, and then read in Hungarian without a dictionary on my way back home to Szolnok, on the train (or, if the event was in Szolnok, then back at home)? Or that translation project would find its way to me through my own response to the book? Or that a favorite songwriter would help me record a song? Or that I would stay at Varga longer than I have stayed at any workplace before, appreciating it more and more, despite the increased hecticness (because of the nationwide increase in required teaching hours)?

But the accomplishments are only part of it. We can delude ourselves with them, thinking that the more of them we have, the better our life has been (and the better we have been). Some of the most important stretches here have little to do with accomplishment. They happen when I am biking to school in the morning and have to stop to take a picture along the way. Or when I sit down to play board games (in Hungarian) with my colleagues on a Thursday afternoon. Or when I sink into a concert, then carry the sounds with me for a long time afterward. Or when a class goes well because of interesting subject matter and the students and me coming together over it, or simply because there’s humor and good spirit in the air. Or when I browse through Eső and find some favorite pieces that then lead me on to other readings. Or when I simply get a good night’s sleep, or taste the first meggy (sour cherries) of the season. Or go on a long, long bike ride and find an active water pump out in the middle of nowhere. Even all of this is just a fraction; what about the kindness I have received here, at school and beyond, from colleagues, students, friends, family, acquaintances, strangers, both here and overseas?

There’s still another level of living here, though, much harder to define, and with no links. It’s the thing that I carry, or that carries me, between the thoughts. Something hinting that there’s still more: not just ahead, but right here. We grasp only a fraction of what is happening at a given moment, but the rest reaches us too. In some way we are made of music.

*I have been told that people trying to access http://www.straightlabyrinth.info/ are receiving security warning messages. This is probably due to a certificate that hasn’t been updated properly. The site itself is safe; it hasn’t been phished or hacked. I will try to get the issue fixed as soon as possible.